Can states bring down vaccine prices? Yes, by coming together as a single buyer

Can states bring down vaccine prices? Yes, by

coming together as a single buyer

A single buyer can always negotiate a lower price for a product with one or more sellers as against a market with multiple buyers. State governments should form a consortium without delay

Updated: May 14, 2021 9:35:04 am

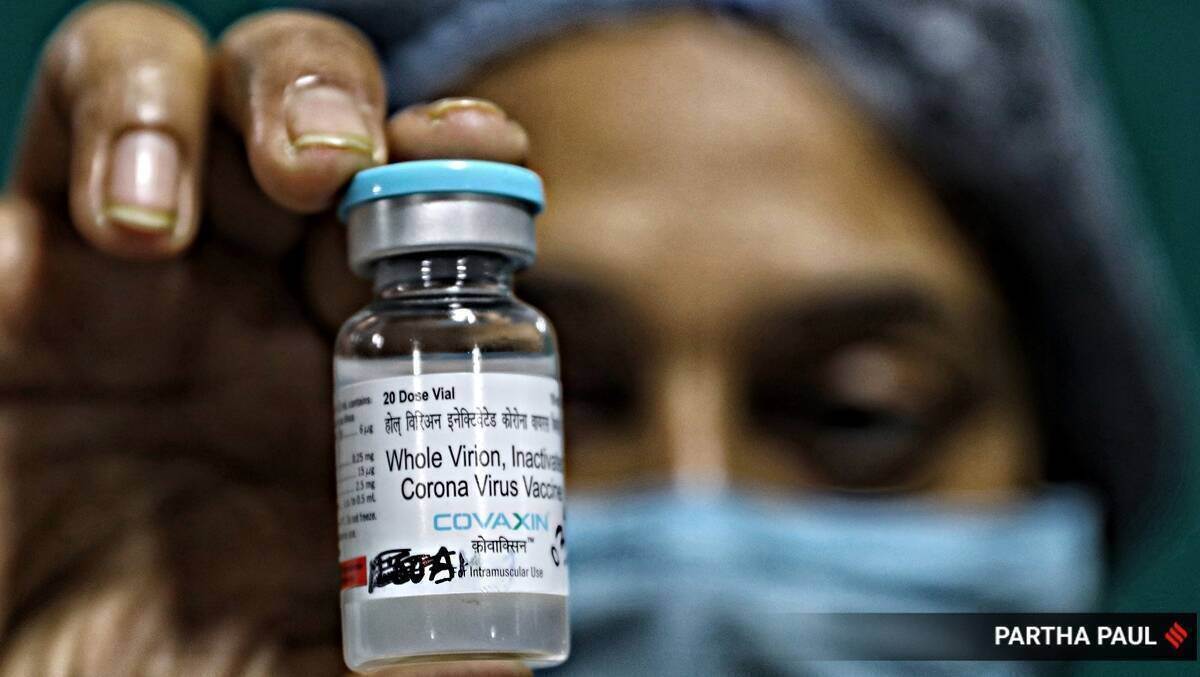

A coordinated effort from state governments is needed to ensure both availability and affordability of vaccines.

A coordinated effort from state governments is needed to ensure both availability and affordability of vaccines.As India grapples with a daily Covid-19 caseload of well over 3,00,000, expedited vaccination is our best hope to flatten the curve. In the initial phases of its vaccination programme, the government of India assumed full responsibility to inoculate the nation. However, with the third phase, it has now transferred the entire responsibility of vaccinating 18-to 44-year-olds, a group that constitutes about 40 per cent of the population, to state governments. For this group, state governments will need to procure vaccines from manufacturers directly. Thus, the market for Covid-19 vaccines has been thrown open and states will now compete with private healthcare facilities to procure vaccines from a limited number of capacity-constrained vaccine suppliers. This shows a complete disregard for economic realities of citizens. A coordinated effort from state governments is needed to ensure both availability and affordability of vaccines.

Undergraduate economics textbooks show that a single buyer can always negotiate a lower price for a product with one or more sellers as against a market with multiple buyers. This result follows the simple logic of “buyer’s power”, which, in this context, dictates that state governments should form a consortium without any delay and initiate pre-purchase orders with vaccine suppliers. This step needs to be expedited on three related counts. One, pre-purchase agreements would tackle any uncertainties from the point of view of vaccine manufacturers and allow for faster expansion of production capacity. Two, any delays will strengthen the position of potential private buyers and weaken the ability of the consortium to negotiate a lower price. A price differential between rates negotiated by the consortium and private buyers then is likely to promote inequity and black marketing that will further widen the vaccination gap between the rich and the poor. Three, this strategy offers a superior mechanism to achieve prices that are affordable in a country that remains predominantly poor and adversely affected by the evolving economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Data from the NSSO time-use survey (2019) suggests that the per capita monthly consumption expenditure for an average Indian is about Rs 1,920. This figure is even lower for the rural sector (Rs 1,672), which roughly accounts for two-thirds of our overall population. Despite SII’s recent “philanthropic gesture” of pricing the vaccine at

Rs 600 ( for two doses) per person, the fact is that these prices constitute more than 31 per cent (36 per cent for rural) of the overall monthly budget of such an individual, which is exclusionary and prohibitive.

Based on a primary survey of willingness to pay (WTP) for Covid-19 vaccines, we find that the current prices are likely to impede rapid vaccination. To study this in context of rural India, which finds itself increasingly at risk, we conducted a primary survey of 1,251 randomly selected households in peri-urban Bhopal between January 30 and February 14. As the virus spreads to the hinterlands, peri-urban areas are likely to be a major source of this transmission. In our study, sample households were spread across 11 villages along the periphery of the Bhopal city. Importantly, these households were located within 25 km of the Bhopal Junction railway station and we found that members from these households relied on regular visits to the city to earn their livelihood.

For a reliable measure of willingness to pay (WTP) and to minimise any reporting bias, we used two popular approaches to triangulate these estimates. These were used in the context of two possible vaccine choices, where one was effective for almost all individuals and the other effective for only 70 per cent of its recipients. We find that the maximum WTP on average stood at Rs 140 for the almost fully effective vaccine, and at about Rs 109 for one with 70 per cent effectiveness. Notably, only 2.2 per cent of respondents were willing to pay Rs 600 or more for the almost fully effective vaccine; and 1.5 per cent were willing to pay the same amount for the other vaccine. About 44 per cent respondents were willing to spend at most Rs 50 for the almost effective vaccine; for the other vaccine, the figure was 56 per cent. Importantly, only 16 per cent respondents were unwilling to pay any money for the almost fully effective vaccine; and 21 per cent for the 70 per cent effective vaccine.

Our survey also found that 66 per cent of the respondents experienced an income shock of over 50 per cent vis-a-vis the past year’s income levels. The WTP declined uniformly with the severity of the economic shock experienced by a household. With the spectre of another economic shock looming large, the economic ability of these households to afford vaccination is severely constrained. Shortage of the vaccine, poor administration coupled with vaccine hesitancy has contributed to an abysmally low rate of vaccination, as per which only 2.8 per cent of the population has been fully vaccinated as on May 12. Leaving sections of the eligible population out of coverage poses further risks of mutations. Universal vaccination must, therefore, be given precedence over concerns of running budget deficits.

Formation of a consortium and provisions for further subsidisation are two critical tools state governments must urgently deploy. On the financial front, curtailing state expenses and creative budgetary solutions like public health bonds offer some solutions for deteriorating public finances. We have already missed the bus on Shakespeare’s advice of “better three hours too soon, than one minute too late”. A minute later would surely be fatal in this hour of reckoning

Comments

Post a Comment